New Boat!

March 25, 2016

My blog has been quiet for a while. Honestly, losing Hales Revenge seventeen months ago really threw me for a loop–probably more so than I’d originally thought. I beat myself up revisiting all the could-haves and should-haves, but in the end just accepted the hard lessons and decided to move on, happy to be alive.

So, please meet Whoodat, a 1982 Tartan 33. We bought her last month and will probably leave her at Elliott Bay Marina in Seattle. She’s a well-built Sparkman and Stephens design. With shoal draft, a fractional rig, moderate displacement, and moderate sail area she rates 162.

Both previous owners took great care of her and updated her continually. We’ve had her out a few times in the bay and found her to be easily driven and well-balanced. I’m getting used to the wheel; I’ve always been a tiller guy. You should see the systems on this boat. Both of the previous owners were meticulous. Dave, the most recent owner, is a naval architect, and everything is immaculate. I thought I’d done a nice job rewiring BackBeat, but the inside of Whoodat’s panel is a work of art. The surveyor pointed out only a few minor items, so that’s good.

Elliott Bay is a nice place to keep a boat. We have a great view of the Seattle skyline and Mt. Rainier, and it’s handy to get anywhere in the Sound within a long day. Port Townsend is about 35 miles North. Victoria is about 35 more. I grew up in Olympia, kept BackBeat there for a while, and like cruising South Sound. Olympia is about 60 miles South, and there are some nice stops along the way if we want to shorten our sailing days. It will really be fun getting to know this boat in the next few months.

The name is interesting. We’d thought it had something to do with the New Orleans Saints Who Dat? chant and fans. The Seahawks have the 12th Man, and the Saints have Who Dat? As it turns out, the original owner had a story involving a family member and a fast boat. I don’t know the details, but “Whoodat” apparently refers to that boat passing everyone like they’re standing still. Think: “Hey, look at that boat go! Whoodat?” Or something like that. If anyone reading this has the actual details, please let me know.

BackBeat is on the hard in Port Townsend. My insurance company totaled it and then let me keep it. I’ll be there next week to get her ready for repairs, and then she’ll go up for sale. Nothing about replacing the broken boom and keel bolts is technically challenging, but it will take a lot of time and care. I always plan carefully, and then double my estimate. I now think that, even with the modifications I made, she’s a little light for oceanic adventures. I’m sure she’d make it to Hawaii, but the trip back is another thing. I really love BackBeat, but when I’m finished she’ll be as good as new and a great boat for someone new to use in protected waters.

Here’s a link to some more pics:

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B8Y6TmAuf3fhT2RIS1BkdWM4OFU&usp=sharing

Here is some info on the design: http://www.tartanownersweb.org/models/t33profile.phtml

Here are some reviews:

http://sailingmagazine.net/article-1027-tartan-33.html

http://sparkmanstephens.blogspot.com/2011/11/design-2348-tartan-33.html

It’s nice to be back on the water. We have plans for the Race to the Straits and Swiftsure in May, and I’m getting quotes on new asymmetric running and reaching spinnakers. Exciting stuff! More later . . .

2014 In Review

December 29, 2014

The WordPress.com stats helper monkeys prepared a 2014 annual report for this blog.

Here’s an excerpt:

A New York City subway train holds 1,200 people. This blog was viewed about 7,600 times in 2014. If it were a NYC subway train, it would take about 6 trips to carry that many people.

Hale’s Revenge

November 20, 2014

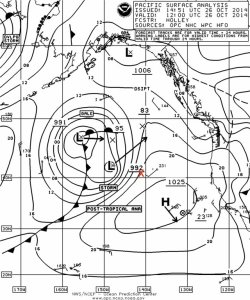

Two experienced sailors and one newb set out October 6th to deliver Hale’s Revenge, an Islander 32–the older, McGlasson design–from Honolulu to Everett. This boat is a heavy displacement, full keel cruiser. It was well-equipped for the voyage. The owner was unable to make the trip, but needed the boat moved ASAP. We had studied the pilot chart, and knew it could possibly be a rough ride, but–well, I don’t know what “but.” We weighed the risks and chose to do it.

It didn’t end well. On October 26, after two other gales, numerous equipment failures, and almost three weeks at sea we were swamped by an irregular wave at about 42N 142W. We’d been weathering yet another storm when it hit us, with a force and from a direction that surprised us. It knocked out our cabin doors, filled the boat with seawater, blew out the portside windows from the inside, and pretty much destroyed the cabin.

We removed the water, but subsequent breaking waves continued to fill the cabin. With more than 800 miles to go, continued depressions on the menu, no way to secure the cabin, no communications, no lights, shredded storm sails, the onset of hypothermia, and chronic seasickness in one crew member and serious injuries in the other, my decision to activate our beacon was easy. The first priority, after all, is to deliver the crew alive.

Hale’s Revenge was low in the water when the two crew were hoisted aboard the Hyundai Grace. Before I left I scuttled her by cutting the raw water intake hose. I imagine it took a day or so to finish going down.

This was a calculated risk by experienced sailors delivering a well-equipped, seaworthy boat. My policy is to draw a line between personal discomfort and safety. I can take a lot of personal discomfort, but I don’t negotiate when safety or seaworthiness are on the line. Especially with other people’s lives. This was just an unfortunate accident.

Experienced sailors will recognize there is more to this story. There always is. I avoided details here because I don’t want a 10,000 word blog entry. If you have questions, please ask them. If you’re really, really curious, ask me for the whole report.

Scaramouche Delivery

September 6, 2014

Wrecking my boat and not starting the solo transpac sucked, but helping a friend and fellow competitor, Peter Heiberg, bring his boat back from Hanalei Bay certainly took the edge off the disappointment.

Scaramouche is a flush-deck racer. Beautiful lines, solidly built in aluminum, and fast. Serious pedigree. Couldn’t have asked for a nicer boat for my first ocean crossing.

We left Hawaii on August 5th at about 0700, with hurricanes Iselle and Julio hot on our heels. Peter has a contact at the Hawaiian Coast Guard station who assured us that their tracks didn’t pose a substantial threat as long as we got North to cooler water ASAP. We shaped a course just West of due North and started ticking off the miles.

The first week was spectacular trade winds sailing, close to 180 miles a day. Iselle eventually hit the big island and died, but Julio seemed to want to chase us. We kept a close eye on him; he came further North than any of us thought he would, but in retrospect never really threatened us seriously. Still, when you’re in the moment it’s a little alarming. I guess now we can say we outran a hurricane. Cool. Don’t want to try it again, though.

Aside from a couple days motorsailing in light variable winds, we had a really nice sail. The crew Peter put together comprised me and two guys from Fort Saint John, B.C., Mike Haggstrom and Joe Brooks. I’d never spent this much time on a boat with other people. You never know how these things will go–I’ve heard some horror stories– but this one was great. All nice guys, easy to get along with, enthusiastic. I’d do three weeks again with this crew any time. It’s true what they say about Canadians. Just really nice, interesting people.

After my misadventure getting down to San Francisco, I’m happy to report there was no weather drama during this trip. During our eighteen days at sea we had some slack days, some more spirited days, some rain, some fog and a few squalls. Nothing we encountered, though, compared to the conditions on the trip down the coast. Thanks, Neptune. You clearly appreciated that shot Peter offered you as we left.

The watch schedule seemed to work well for everyone. Mine was 6-9, morning and evening. That seemed like one of the better ones; next time I should probably offer to take the 12-3 or the 3-6. I’m used to being up all the time when I sail alone, so night watches don’t bother me. Still, no one complained. Again, the polite Canadian stereotype is well-earned.

We took turns cooking and, thanks to the provisioning prowess of Christy McLeod, Peter’s significant and much better looking other, we ate pretty well. We had enough ice aboard to keep fresh foods for about a week. After that we had a nice variety of canned, packaged, and freeze-dried meals. I lost some weight, but that’s probably because there is no drive-through at sea. It was a total score to find two huge chocolate bars in the snack cupboard about halfway through the trip. I also determined–the uncomfortable way–the shelf life of unrefrigerated Activia yogurt.

Peter had set the boat up really well for the race, so there were no significant gear issues on the trip. Rigging, navigation, electrical systems and communications all worked fine with no complaints. There was one early morning alarm when a belt broke on the motor, but Peter had that repaired before I came up for my 0600 watch. We had a temperamental plotter at the helm, but Peter also has a heavy-duty nav program on a Panasonic Toughbook at the nav station. We tried to get some of the other returning yachts on the SSB, but no one ever seemed to be home. AIS was useful for avoiding ships, which we had close approaches with on a few occasions.

By Saturday the 23rd we were closing in on Tatoosh Island. The wind had died, so we were motoring at about five knots. Fog lay on the water like a thick blanket, and when night fell we found ourselves in zero visibility. The watches were nerve-wracking, because the offshore fish boats don’t all use AIS. Peter was basically navigating an instrument approach to Neah Bay, where they planned to drop me off before continuing on to Victoria. As we passed Tatoosh the wind came back a bit and the fog began to lift. We entered the bay, made our way to the marina, and tied up at an end slip.

That was it. It was about midnight-ish, and after days of looking forward to landfall my trip was over. Julie and Penny were waiting for me, so I scrambled up to the parking lot. Being on land again was kind of weird, a little anticlimactic. You’re at sea with people for three weeks, anxious to get home, and then in just a second you’re not. You really get used to the rhythm of wind, waves, watches, galley duty. Then it just ends. I was super glad to be home and see my family, but the transition was abrupt, kind of surreal. Except for the part about missing my family, I don’t think it would have bothered my to turn around and do three more weeks.

Peter tells me he wants to sell Scaramouche, that after a lifetime pulling sheets he’s through with sailing. He and Christy have a new project, and cruising plans that don’t include sails. Scaramouche is a well-found, go anywhere on the planet boat. It doesn’t need anything that I can think of. You could buy it tomorrow, sail it past Tatoosh Island, and go anywhere safely and comfortably. If you’re reading this and are interested, contact me and I’ll forward you Peter’s contact info.

Fast is Fun!

July 30, 2014

That’s the official motto of people who race ultralight boats. BackBeat is neither an ultralight nor a sport boat, but she can get up and go in the right conditions. With a masthead kite, wind over 15 knots, and a decent swell to surf, she’ll easily hit 10 to 12 knots. The highest I’ve recorded is 14.3. That was running with just a double-reefed main in 30-ish knots and combined seas of 12-16 feet. Fast really is fun. Here’s some track data.

The Gory Details, Part II

July 15, 2014

I reread part one of this adventure to remember where to pick up the story. With a comfortable buffer of time and distance, my first account now seems kind of dramatic. That’s how it was, though, and you want to get these stories down before too long, or time will change the details.

Michael Jefferson, a Transpac veteran, was among the first people I met when I got off the boat in Alameda. He and his mate, Susan, collected my sorry ass and took me out for some dinner and company. He has this theory that people enjoy their pastimes in one of two broad ways. The type-one folks do something fun and enjoy the moment. These are your gamblers, golfers, titty-bar patrons, and whatever. Type-two people submit themselves to all manner of punishments before they register their fun. It’s misery, and in the moment you may hate what you’re doing and swear to change your ways and take up golf, but within a few days of surviving you’re remembering the experience differently, and can’t wait to get back out and do it again. Type-one: I went fishing, which was fun. Type-two: I got my soul crushed in a gale off Mendocino. I survived, and now that the edge is off I want to go do it again. There is a type-three fun-lover. All he’d say about that is that the type-three folks sometimes don’t come back from their adventures.

So, with a little less adrenaline in my veins, here’s the rest of the story. We ended part one with:

“Right on cue, about 20 miles NW of Mendocino , the wind started to build. I don’t know what you call it when you know something bad’s about to happen, but you sit there and do nothing, hoping it won’t. Inertia? I don’t know.”

Andrew Evans singlehands an Olson 30. He wrote a book about it, which I found tremendously useful, and which you can find here:

http://sfbaysss.net/resource/doc/SinglehandedTipsThirdEdition.pdf.

Rereading his book last night, I spent some time with his discussion of what he calls Emotional Inertia. This is exactly what happened to me as I approached Cape Mendocino.

You’ll remember that I had my spinnaker up. The weather was fine, but all the information I was getting predicted high winds and heavy seas, and soon. I knew I should probably take the spinnaker down, but I didn’t. As the wind increased the boat was regularly hitting 13-14 knots. It was the middle of the night, and bioluminescence was spraying from my quarters like streamers. I felt like I was on another planet. It was really, really cool.

Part of me figured I’d enjoy this as long as possible and then douse the kite, but another part of me was just stalling because I was terrified to get out on the deck and do the work. By now the motion of the boat was pretty active. It’s hard to describe to non-sailors, but let me try. Being on the deck of a small boat that’s pitching and rolling in high winds and big waves is kind of like trying to kneel on the back of one of those mechanical bulls you used to see in bars. You need all your energy and both hands just to hang on. Yes, the foredeck is a little wider than the back of a bull, and its movements are a little slower, but that’s about the size of it. Now, besides trying to hang on, try to get some work done. No thanks.

Andrew Evans nailed it with the Emotional Inertia theory. In this case I knew that waiting to douse the kite could only lead to grief, yet I pressed on, doing nothing and hoping for the best. What eventually happened was that I got the kite down, but it wasn’t pretty, and it was torn all the way across the foot. That happens when you catch it on something and then let it drag through the water while you try to pull it in like a gillnet.

By now it was about four in the morning. I had the main out to port with a double reef, and was still hitting 14 knots. The autopilot was actually steering pretty well after I turned the rudder gain down all the way. I was beat, so I went below to catch a few Zs. Big mistake number one. It wasn’t ten minutes before I crash-gybed. It was loud and violent; I thought the whole rig had come down. I bolted out of the cabin, gybed back to starboard–properly this time–and got the boat trimmed again.

Now what? I really needed to get some rest, but I was, I’ll admit, paralyzed with fear at the thought of going back on the foredeck to set the storm jib and take down the main. Getting the spinnaker down had just about wiped me out, so I figured I’d put a preventer on the main and come up a bit to avoid another gybe. The storm jib would have been a better idea but, well, inertia. And the main was already up.

Big mistake number two. Preventers should go on the end of the boom, but my end was way out over the water. I couldn’t reach it with my tether clipped in to the cockpit padeye. I clipped on to the port jackline and stood on the sidedeck to try to reach it, but a wave hit the boat and I lost my footing. For a few seconds I had my arms wrapped around the boom with one foot on deck and the other in the water. I hooked my left boot toe around a stanchion and used every ab muscle I no longer have to get my weight back on deck and into the cockpit.

Screw trying to get a line to the end of the boom. Have you ever been in a situation where you’re so tired and so pissed off that you make a decision you know is bad? That you know people will criticize you for, and that may damage the boat, but you just don’t give a shit anymore? Well, that’s where I was when I got a nylon line and carabiner out of my line bag. At least nylon is stretchy, I figured, as I tied the line around the boom. I don’t have a good spot to put a preventer mid-boom on this boat, but there are some clam cleats on the boom that would prevent my clove-hitch from sliding back toward the vang–or so I thought.

I was hand steering now in apparent winds in the high twenties. It was actually pretty comfortable, so hoping for the best did not seem unreasonable. The seas were huge, steep, and short, but at least they all seemed to be coming from the same direction. Keeping them directly astern was going to take me right past Cape Mendocino and generally toward Pt. Reyes, so I just settled in and steered by the waves instead of the compass. I figured I’d ride the waves until I got close, and then tuck into Drakes Bay, behind Pt. Reyes, if I needed a break.

It was still dark, and I was still trying to stay square to the waves, when a wave seemed to come out of nowhere and hit me on the port beam. I could hear it hissing just before it hit; there wasn’t anything to do but turn my back to it and brace myself. It felt like someone turned a fire hose on me. I flew across the cockpit, hitting my left shin on the starboard winch. I had one hand on a stanchion and the other on my tether, trying to stay in the boat as it went over. It seemed to take forever, but I’m sure it was only a few seconds before the boat came up.

When it did the main was backed. I had no idea where the boat was pointed, but I grabbed the tiller and tried to muscle it around so I had the waves astern again. Nothing seemed to help, so I decided to let the preventer go, let the boat crash gybe again, and sort things out when I could get control.

Big mistake number three. I had clipped the carabiner at the deck end of the preventer to a stanchion base. They can’t be opened under this kind of load, and now that I knew what kind of loads a main backed in this kind of wind could generate, I was afraid the stanchion was going to pull through the deck and come at me like a missile. Just as I was reaching for my knife to cut the line, the clove hitch I’d tied in the middle of the boom slid over the cleats I’d “secured” it behind and slipped back toward the vang fitting. The boom swung about two feet to starboard, and then folded like a lawn chair.

The boat immediately stood up. I just sat there, stunned. The main was tangled in the rigging, but still projecting enough surface to keep some way on. Still, I just sat there. That was a weird feeling. You know you’re not going to die, but you know you’re pretty screwed. I was steering the boat without even caring where I was going. Time seemed to stop as I rolled all of the possibilities around in my head, and I figured my race was over before it even started.

It must have been twenty minutes or so before I got my shit together and went into problem-solving mode. It was clear that the main wasn’t in danger of shredding on the rigging. It was driving the boat at nearly six knots, so I just left it up that way and hand steered until long after the sun came up. When the wind finally abated, I untangled the main, shook out the reefs, and cut the clew loose from the twisted boom. I attached the spinnaker sheets to the clew and flew the main loose, kind of like a genoa.

That actually worked pretty well. The wind had dropped to the high teens and low twenties apparent, and by the time I’d passed Pt. Reyes I calculated that I could get inside the bay by about 1300 or so with this rig. There was some damage besides the boom. The spare battery had gone flying around again, and I was pumping water out of the bilge again, but I seemed to be in one piece, and the worst seemed to be over.

The rest of the trip was relatively uneventful. After all the previous night’s excitements, I was finally settling down and enjoying the sail. I saw a few charter fishing boats and wondered how their passengers were doing in the conditions. I started noticing the pelicans that had been there all along. As I got closer to the Golden Gate Bridge I could see coastal water bumping up against the blue water. It was weird–almost like someone had dumped greenish paint into the bay and let it spread into the ocean. The boundary between the two was abrupt and distinct. Beautiful, but weird.

Brian Boschma, from the SSS Race Committee, called on the VHF to welcome me as I was nearing the bridge. I didn’t enter the shipping channel, which I later found out was not very smart, but kind of cut the corner at Pt. Bonita, where I dodged some gnarly looking rocks. I found out later that that wasn’t a good idea either. Well, any ending you can walk away from is a good ending in music, so I’m applying that motto to this clumsy approach too.

I sailed under the bridge at close to slack tide. The wind was now about 18-20 knots from the NW, which was perfect for riding the swell coming in behind me. Brian had invited me to stop in at the St. Francis yacht club to say hello and take a break. I pulled in, tied up, sat down below, and promptly fell asleep. When I awoke it was getting late, so I headed out again to get into my slip at Marina Village early enough to register and get a bathroom code. Along the way I made an attempt to straighten out my boom.

It was no use. People on boats in the estuary looked at me like they were wondering what in the hell had happened. After a brief chat with a skipper coming in on an Ericson 38, I decided to sport my broken boom like a badge of honor. Really, what else can you do?

Within half an hour I was at Marina Village looking for slip E7. If you’ve never been there before the layout is kind of confusing, but a few U-turns later, and with the gracious help of my new neighbor, Matt, a liveaboard, I was tied up.

There’s more to tell, but a thunderstorm is rolling in, and I’m going to go enjoy it with my dog. BackBeat out.

BackBeat on the DL

July 11, 2014

So, I guess I’ll be looking for a new BackBeat for the 2016 Singlehanded Transpac.

I met a guy in Alameda doing the Pacific Cup on a Hobie 33. We were talking about the cost of these races when he said “You buy these boats for $20,000 and put another $30,000 into prepping them, and then you’re left with an $18,000 boat in the end.” My numbers are a little smaller, but that’s the truth about ocean racing.

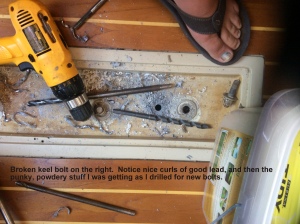

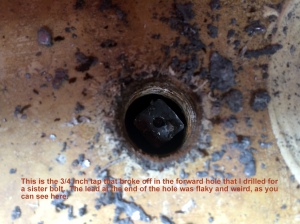

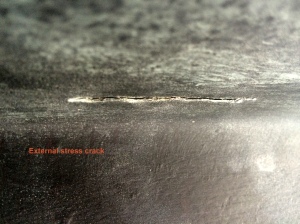

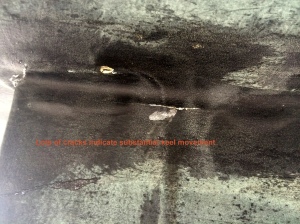

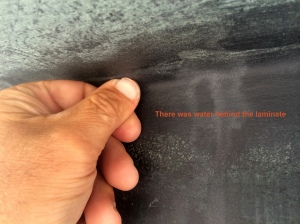

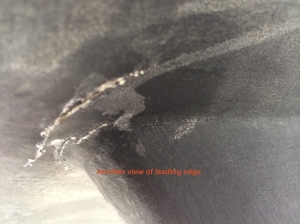

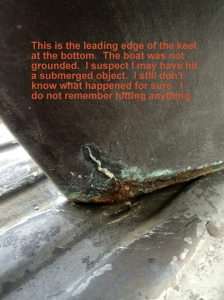

BackBeat suffered some damage on the way to San Francisco from Port Townsend. Dead autopilots, shredded spinnaker, broken boom, and a broken keel bolt. It turns out the keel issue is far worse than I’d thought, and it’s looking like my insurance company may total out the boat. No matter how much you have into the project, they’re not going to pay out more than the boat is worth, and that’s the deal you sign up for when you pay your premium.

I’ll be able to buy her back for a salvage price, so the plan now is to bring her back to Spokane and put her in storage until I have time to do the keel repair myself. There’s not much in the way of materials–some glass and epoxy, a few expensive drill bits, and some keel bolts–but the time involved will be extensive. The yard rate is $90 per hour. My time is an investment into a cool hobby, and when she’s fixed she’ll be a great lake and bay boat.

Here are some (probably too many) pics:

Road Warrior

July 7, 2014

Got the boat back to Port Townsend Boat Haven at 0100 yesterday morning. When you’re injured it’s nice to be in your own home. The trip kind of sucked. Towing this thing is extremely stressful. I don’t know if it was the traffic around the bay area, the July 4th traffic on the highways, or the horrible gas mileage, but I had a headache and ground my teeth all the way home

Anyway, I’m glad BackBeat is home. Tomorrow I need to deal with all the damage and get home to Spokane.

Getting To The Starting Line–The Gory Details

July 1, 2014

The trip to San Francisco was like nothing l had imagined. Despite what I considered careful planning, I had either too much wind, too little wind, wind from a direction that hadn’t been forecast, seas that bore little relation to the forecast, equipment failures, and a minor existential crisis. Still, I made it mostly alive. Here’s the tale.

June 9th, Departure

Check this out. I’ve got the boat loaded and ready to go, and she’s sitting on her boot stripe. This is after I’d carefully considered everything on the boat and made several trips back to the car with things I decided I wouldn’t need.

I left Port Townsend early Monday, catching the last of the ebb. The forecast for the Eastern entrance to the strait was 15-25 knots from the NW, so I had a reef in and a heavy weather jib up. I expected the current to change soon, but when the wind comes straight in like this the waves tend to lie a little easier with the flood than the ebb. My boat is light, and going to weather is tough when wind and waves conspire against your progress. A botched tack can stall the boat and set you back a quarter of a mile before you get her pointing again. I figured the worst that could happen if I left in these conditions was that I’d get a beating trying to make 3.5 knots motorsailing to weather.

Well, that’s exactly what happened. Jak Mang, on Maitreya, had left Port Townsend four days earlier for the same race and had more settled weather. I was reminded once again that a calendar and a deadline are two of the worst things you can have on a boat.

So I sailed. I motored. I motorsailed. More than twelve hours into this leg I’d only managed to get about halfway between Crescent Bay and Port Angeles. That’s not great. The wind was blowing a solid 25 now, with higher gusts. During one particularly gusty tack I lost control of a sheet, which flew around, snapping and cracking like a cowboy whip in a wild west show. Trying to grab it was a mistake; when it hit my hand it sounded like a gunshot and felt like a hammer blow. I eventually got the jib trimmed and looked at the knot meter. The high wind alarm had gone off. Check it out.

With night falling in the shipping lanes, fifty some miles to go to Neah Bay, and a new respect for the wind gods, it was an easy decision to turn back and run off to Port Angeles. I got the boat secured, had something to eat, and turned the heater up to try to dry everything out. I noticed water in the bilge as I was cleaning up. It came out easily with the pump and a sponge, but I was a little alarmed at the amount. It stayed dry overnight, though, so I turned up the optimism and resolved to continue. I really hoped this little weather snit would blow itself out by morning.

June 10th, Day Two

It didn’t, but what could I do? It looked like the strait was in for several days of high NW winds. I had places to be, so I set out once again, early, to try for Neah Bay.

More sailing, motoring, and motorsailing eventually got me to Neah Bay just before nightfall. It was a bone-jarring ride. Teeth rattling. Generally unpleasant. There was more water in the bilge, and I was a little concerned about my keel joint. My spare battery had broken its moorings and was lying on its side in the bilge. I was exhausted and a bit rattled.

It made me happy to see a pair of sea lions lounging on a dock, so that’s where I tied up. I thought it would be cool, like parking next to a zoo exhibit.

That lasted about half an hour. I don’t know whether these two were fighting or flirting, but good lord they were noisy. I soon determined that I was on the commercial dock, where the only power available was 50 amp, so I moved the boat to a more habitable finger.

Here are some Neah Bay pics:

Tuesday night in Neah Bay was pleasant. I dried things out, bailed out the bilge water I’d accumulated, secured my wayward battery, and got some rest. I checked all my safety gear and found that the CO2 cartridge in my favorite PFD was bad. I didn’t have a spare on board, so I moved my knife, PLB and strobe to my harness and got one of the guest PFDs ready to use. I also filled the outboard fuel tank and stocked up on candy bars at the gas station. Looking back I figure I missed Peter on Scaramouche and Jak on Maitreya by just a few days. Too bad. We all got a beating going down the coast, and it would have been nice to have the advice of these more seasoned sailors.

The last thing I did Tuesday night was look at the next day’s coastal weather. 5-15 from the NW with a four-foot NW swell seemed pretty reasonable, and my plan was to get out to about 127 to avoid the compressed isobars further down the coast.

June 11th, Day three

Wednesday morning dawned calm. No wind at all. Not even a ripple in the bay. That calm water in the pics above seemed to extend well into the strait and past Cape Flattery, so I motored around Tatoosh Island, put the sails up, set a SW course, and then sat there parked for several hours. I finally fired up the outboard when the current started pushing me back toward the coastline.

My outboard gets about 18nm per gallon. I had eight gallons aboard, so I figured I could motor about 120 miles and still have a good reserve. That’s what I did. Several boring hours passed quietly. I don’t remember when the wind picked up, but I do remember getting the weather with my sat phone and seeing how much had changed since I left Neah Bay. Now, instead of 5-15 from the NW the prediction was 15-25, with small craft advisories for high winds and hazardous seas.

The wind I got was pretty much from the NW, as predicted, but I was seeing high 20s on my wind indicator, and that’s with 8-12 knots of boat speed at about 150 degrees apparent. And the seas, OMG. NOAA had called the swell at eight feet with combined seas of at 12 feet. I don’t know what they were smoking when they put that out. First, the swell and waves did come predominantly from the NW, but there were other wave trains that collided with them, and the whole sea seemed like it was frothing and exploding. I saw a bulk carrier pounding North at about 126W. It did not look comfortable. About every eighth wave its bow would bury in a spectacular explosion of white water.

By now I was running with the waves with just a double-reefed main and trying to steer through the mess without crash gybing. I could have sworn some of those waves were more than 20 feet high and, as it turns out, the way NOAA defines significant wave height allows for the possibility of seas up to twice the predicted value. Yup, they were big.

I got through most of Wednesday night with the autopilot, but by Thursday morning it had started making unfamiliar noises.

June 12th, Day Four

Wednesday night’s moon was pretty big, and I thought I could see pretty well, but Thursday morning was a shock. If the seas seemed big at night, at least I could only see the wave directly behind me. Even before the sun came up, in the grayish light before dawn, I could see pretty far back and it wasn’t pretty. By now I was alternating hand steering with the autopilot. My assumption was that the unfamiliar noise I’d been hearing could only be bad, and sure enough, later that morning, the autopilot motor just started spinning. It appeared to respond to commands from the brain, but the actuator wouldn’t budge. Shit. I wanted to heave to so I could get below to get the spare but, frankly, the thought of trying to come about in that wind and those waves scared the crap out of me.

The rod was stuck at about the middle of its travel, so I pinned it to the tiller and dove below to get the spare autopilot. I was surprised to get back to the helm to find that the boat had pretty much held its course. I mounted the spare, and it was smooth sailing once again.

For a few hours. My boat is kind of twitchy in following seas. This makes the autopilot hunt for its course. I had the manual in one hand while I tried out various rudder gain settings. Both this one and the original had been set at a value of four, which I came to by following the instructions for commissioning the units in relatively calm waters. It had worked fine in every condition I had encountered up to the huge seas and high winds, where I found that a gain setting of one gave me the best performance. Still, the spare pilot failed within hours. This one made no noise at all, but just stopped responding to commands. I could tell that the motor had failed because the only sound it was making came from the off-course alarm.

Now what? Well, first I got the boat under control and continued on my course hand steering through the waves. That bought me time to think and look at my chart. There was no way in the world I was going to hand steer the rest of the way to San Francisco. Heading toward Astoria would have meant a long windward slog. The nasty Columbia River bar was prominent in USCG sécurité broadcasts, so that was out anyway. I settled on Newport, Oregon. It was south of my position and looked like a place I might find someone to repair my autopilots.

The next sixteen hours or so are a blur. I hand steered until it started to feel unsafe to be at the helm. I was exhausted. I’d heaved-to to rest several times, but I wanted to try a drogue. My oldest son, a marine canvas guy, had made me a nice ladder out of seat belt webbing. I use it to climb my mast solo and it works nicely. I’d anticipated that I could also use it as a drogue if I needed to, and I had the parts aboard, so I rigged it up. I made a bridle out of extra line and attached a 150 foot nylon anchor line. After that came the ladder, and then an eight pound mushroom anchor on a twenty-foot cable at the end of it all. I payed it out with the storm jib up, and was amazed how nicely the boat rode. The advantage over heaving to was that I could use the bridle to get the boat to point in the general direction of Oregon without constant attention to the tiller. Heaving-to seemed like a more temporary way to rest, and I when I did I just drifted kind of generally South with the wind and waves. With the drogue out I was making from one to three knots, and felt like I could point the boat where I wanted it. The motion was easy, and when I needed a quick break I tied the tiller off with the rudder centered.

June 13th (Friday), Day Five

Winds were still high and the seas were short and steep. It was miserable. I rode the drogue when I was tired, and pulled it in when I wanted to make some time under sail. I’d guess I pulled the drogue in four or five times altogether, and I found that it was easy to get back on the boat if I waited until I was in a wave trough. Then I’d pull in as much as I could, cleat it off, and wait for the next trough. I worked my way toward Newport this way, but I felt more like I was surviving than sailing.

Sometime Friday night. Drogue is out. I’m wedged sideways in the boat with my head under the deck. I could feel hypothermia coming on, so I’m bundled up trying to get some energy back so I can go out and steer again. This totally sucked.

It was awful. At one point I was curled up in the bottom of the boat thinking about firing my EPIRB just so someone would come and get me out of this. I didn’t, but I thought about it for a long time before I got it together enough to go out out and sail the boat just one more time. This is about the time I absolutely knew that if I made it to Newport alive, I was going to sell the boat and take up golf. Or walking. Hell, any sport where the ground is solid under your feet.

June 14th, Day Six

When the sun rose Saturday the wind and seas seemed to ease a bit. I was still about sixty miles from Newport. As I got closer to the coast the wind dropped until I was only making about four knots. Yes, I could have put up the spinnaker and made hull speed toward Newport, but at about forty miles out I fired up the motor. The closer I got, the less wind I had, and aside from another nine hours of hand steering, Saturday was actually sunny and pleasant. I made it to Newport by early evening.

When I stepped onto the dock I was wobbly and weak. I had a line ready, but the wind caught the boat and it drifted just out of my reach. I thought for a minute about jumping for it, but I just stood there watching it float away. I thought for another minute about jumping in and swimming to the boat, but still I just stood there. To tell you the truth, if it had floated out the channel and I’d never seen it again, that would have been fine with me. It was drifting across the marina to another finger, though, and my new neighbors, who had seen me come in and were watching this comedy, ran around and caught it for me. The guy’s name was Andrew, and I don’t remember his wife’s name. They were in Newport waiting for weather to get North to Seattle, and I really owe them. Who knows how many boats mine might have bounced off of and damaged before it came to rest somewhere. Andrew, if you’re reading this, I hope you made it to Seattle safely, and thanks again for all your help.

An hour later I had the boat put away and was crashed. I hadn’t really eaten or slept since Tuesday night, and I was beat.

June 15th, Day Seven

Well, this was the day I’d originally hoped to be in San Francisco. Ha ha ha. Nature clearly had other plans for me. Not much to do on a Sunday in Newport, Oregon, so I phoned a few of the numbers I’d gotten for possible autopilot repairs and did some serious housekeeping. One guy called me back to tell me that there was no one in town who could repair an ST2000 tiller pilot on short notice. Newport is a commercial boat town, and all the dealers cater to them.

Hearing that news, along with general boredom and a little anxiety about getting to San Francisco on time, motivated me to open up the two dead autopilots. It turns out they’re not as complicated as I’d thought, and I was able to piece together one functional unit from the two dead ones.

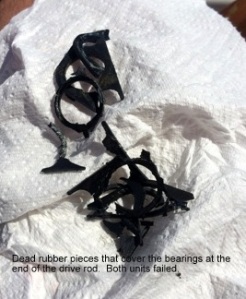

Drive belt failed on the first and on the repaired autopilots. Turns out this is a common failure, and Raymarine will not sell parts to end users. Something to consider if you buy Raymarine.

Poor alignment from the factory caused the second motor to burn out. It was two to three millimeters off. Bad QC I guess.

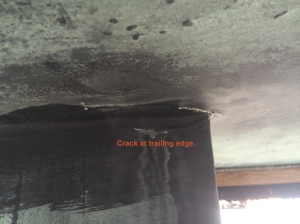

This is not supposed to look like this. The loose piece is normally pressed in and seals the bearing race.

This is the first unit that failed. I couldn’t reuse the cracked case so I moved all the remaining good parts into the back up unit and saved all the bad parts for the warranty claim.

Other than that Sunday kind of sucked. It was Father’s Day, and I was in a tough spot, far from home with none of my family around. At least the Rogue Brewery was close at hand. I stopped in for some over-priced fish and chips and a Dead Guy Ale.

June 16th, Day Eight

The first thing I did Monday morning was order another autopilot from Port Supply and arrange for it to be shipped overnight to the marina office. The rest of the day I walked around Newport, watched movies, and chilled. The only other noteworthy thing I did Monday was drop the mushroom anchor on my left big toe. That left a mark that I can still feel as I write this.

June 17th, Day Nine

Hung around, picked up the new autopilot from the marina office, got ready to leave with the tide at 1700-ish. Left with the tide at about 1800, motored out past the jetty, and set a Southerly course that would keep me within about fifty miles of the coast. By now I was freaked out about the autopilot issues and kind of worried about the keel, so I wanted to stay close. There was no wind, so I motored for several hours. When the wind did come up it was flukey and light, so I basically motored or motorsailed most of the way to Coos Bay, where I pulled in for about an hour to refuel. Nothing more to report.

June 18th and 19th, Days Ten & Eleven

I’d made Coos Bay late in the morning of the 18th and was gone, with full fuel tanks, by noon-ish. I cleared the jetty and set a Southerly course again. Between Coos Bay and Mendocino there was nothing unusual to report. I had 15 to 18 knot winds varying from 150 to 180 apparent. It was nice and I was making decent time. The repaired autopilot was working nicely, and all was well with the world. The worst thing that happened was that I popped up to look around once and saw that I was headed straight for a fishing boat about 300 yards away. I changed course, but there were several other boats in the area, and not one of them was transmitting an AIS signal. I spent the next several hours slaloming through this minefield of boats.

June 20th, Day Twelve

I was cruising along at a pretty good clip in about 15 knots apparent. The autopilot was driving, and I was looking at weather I’d downloaded on the sat phone. It said that Cape Mendocino was going to be ugly. That was hard to believe because I wasn’t that far away, and I was in pretty nice conditions. I didn’t see anything in the GRIBs that looked that bad. I turned on the VHF weather and heard the same report though. I decided to keep my spinnaker up as long as possible. I don’t know why; it wasn’t a good move.

Right on cue, about 20 miles NW of Mendocino , the wind stared to build. I don’t know what you call it when you know something bad’s about to happen, but you sit there and do nothing, hoping it won’t. Inertia? I don’t know.

7/1/14, 05:30. Oops, have get on the road to go get the boat. I’ll post part two when I get back.

Sea Life

June 30, 2014

I saw thousands of these. Yes, thousands. Maybe millions. Every time a wave broke over the boat it left their little bodies behind, and the blue part left ink spots on the deck until the next wave washed them away. Strange looking creatures. They were completely at home in the conditions, and I envied them that. They’re called sail jellyfish.

When conditions were at their worst, a black footed albatross seemed to hang around to keep me company. Yes, I know it was probably just looking for scraps of food, and yes, I know that it probably wasn’t the same bird every time. I also know that it couldn’t care less about me, but it gave me some comfort at the time to imagine that it was checking in on me. “Hey, dude. You look like you’re having a rough time. I live here. Anything I can do?”

These dolphins are fast. They too came around to check me out and stayed a while. Again, I liked to think they were there for moral support. They played a game where the port side dolphin would shoot forward and dive under the boat, in front of the keel, and pop up on starboard. Then the starboard dolphin would do the same thing and pop up on port. Cross, repeat, cross again. In high winds and huge seas, while I was wondering what in the hell I was doing in a small boat, they were playing backyard dolphin games. Super cool.

It’s interesting that you don’t see as much of the albatross as you get close to land, and you don’t see many gulls as you get out to sea a ways. Saw lots of pelicans close to the coast, and a few puffins up near Cape Flattery. I don’t know anything about sea lions, but I never imagined them far from shore, so I was surprised to see one pop its head up about sixty miles out.